Bangladeshi Cinema

People were making films in Bangladesh as early as 1919, when it was part of India and under British administration. However, at the time, all production was based in Calcutta. Dhallywood’s journey, often referred to as the films of Bangladesh, began in 1956 in the heart of the capital, Dhaka. The first Bengali feature film in Dhaka (East Pakistan), ‘Mukh O Mukhosh’ (The Face and the Mask, 1956), marked the beginning of the journey. Despite initiating production in 1953, filming faced delays due to inadequate instruments and funding. Despite a lack of resources and restrictions, this film became a huge hit, with Bengali crowds flocking to theaters to see the region’s first film.

Filmmakers in Bangladesh have long strived, since the establishment of the country’s film industry, to showcase the country’s stunning natural scenery through spare narratives. It was never easy, however; the influence of western and Indian culture, a tendency to mimic Hindi films, the use of sexually explicit language or women to attract an audience, and a lack of funding were all obstacles that prevented the Bangladeshi film industry from producing high-quality films. Despite this, a handful of filmmakers in Bangladesh have improved the country’s film industry. Famous Bangladeshi filmmakers like Zahir Raihan, Tareque Masud, Tanvir Mokammel, Morshedul Islam, Humayun Ahmed, Tauquer Ahmed, Chashi Nazrul Islam, Mostofa Sarwar Farooki, and countless more did more than make movies; they battled to preserve their culture through cinema. When discussing a single director’s cinematic language, it may seem strange to include a young filmmaker like Mostofa Sarwar Farooki among the forefathers of Bangladeshi cinema, but as we delve deeper into his cinematic identity, the impact of his storytelling is immensely noteworthy.

Just by watching Farooki’s movies and dramas without seeing his name, anyone can notice it’s all ‘Farooki’, driving the storytelling narrative. All of his films and TV shows follow a similar trend: a satiric representation of a community where the characters speak to each other on a more personal or local level and sprinkle in a dash of humor. Farooki’s films mirror the style of Italian Neorealist films in many ways. His characters are often simple, and the dialogues are filled with humor, which makes Farooki’s works enjoyable. His prose, and sometimes even his stories, are more effective at engaging readers than his images. Three of his films stood out from the rest because they were so unlike anything else coming out at the time. Doob (2017), Ant Story (2013), and Television (2012) revealed fresh ideas to society, offered stories about our environment, and shed light on his cinematic perspective.

Doob: No Bed of Roses

Farooki’s Doob was released in 2017. It featured some of the best actors of their generation, from India and Bangladesh. The story centers around Javed Hasan, a filmmaker, and his family. A midlife crisis causes Javed to doubt his marriage and his professional decisions. Javed’s extramarital affair with his daughter Saberi’s childhood friend, Nitu, garners national media attention, leading to the disintegration of his family. He gets a divorce to marry Nitu, separating himself from his children, but soon realizes that life isn’t going according to plan. In contrast, Saberi, who is Javed’s daughter, is assisting her mother in embracing her newfound independence, adapting to unique situations, and drawing strength from their shared struggles.

Doob is a breathtaking film that goes above and beyond what I expected. The most impressive parts of the film, in my opinion, are the spectacular sequences that the filmmakers worked very hard to make seem as realistic as possible. Let’s take the first scene of the movie, for example. The female leads, Saberi (Tisha) and Nitu (Parno Mittra), reunite at a school reunion after a long time apart. When they were in school, they were best friends. Now, they sit quietly together without speaking a word. A reunion is usually nostalgic, recalling old memories, uncontrollable laughter, and fond recollections. Nonetheless, the scene plays out differently. The plot unfolds and culminates in a major flashback. In the years since then, many events have occurred. While blaming one another, Saberi and Nitu each suffer the loss of loved ones. From a personal perspective, it seems fate may have different intentions for these two; at least that’s what I like to believe. They are both young, charming, and talented individuals. Perhaps this reunion represents something new and hopeful: the reestablishment of a friendship and the rekindling of old memories.

Doob’s cinematography also contributes to its beauty. A natural smoothness pervades the entire film, with some outstanding shots of the individuals. Every shot in the film told a story about the characters, their motivations, and their emotional states. Take this shot as an example: Farooki emulates a scenario for Javed in which he is vulnerable, lost, and alienated. This is a stark contrast to the stereotypes most people hold about men in general. Farooki intended to highlight men’s loneliness while also demonstrating that men may be sensitive in every aspect. Society expects men to be powerful, aggressive, and mentally and physically active at all times. With this single shot, Farooki was able to depict the character’s loneliness without the need for any buildup, speech, or mention of any happenings.

Doob introduced a new way of expressing stories about people’s emotions. The film is a sensitive piece of work. For some, as a Bangladeshi film, it may appear slow or lengthy, but it will undoubtedly present the viewer with certain common concepts of life and existence. Furthermore, it is a family film, so you may see it with your loved ones and experience the tragedy of life as a whole.

Pipra bidda (Ant Story)

In “Piprabidya,” Mostofa Sarowar Farooki picks an ordinary man and attempts to tell an extraordinary story within his visual realm. With a small cast and a complex narrative, Piprabidya dishes out a plateful for proficient filmgoers but is unlikely to appeal to the general public. Without revealing the plot, “Pipra Bidya” tells the story of internal conflicts and a man’s deliberate isolation from reality. Another essential characteristic that Farooki has exploited cleverly and maturely is the different shades of the same personality. From my perspective, the film’s cinematography was quite experimental. It was not the typical beautiful camera shot we see in Farooki’s films. Rather, he introduced a new standard for telling stories using different lenses. A few high-angle shots depicted the protagonist’s mischievous activities and tense moments in the film. The film contains many positive aspects, including a dash of dry humor and elements of a psychological thriller. Chirkutt’s eloquent music helps the narrative come to life for the viewer. The story, however, is not presented to them on a silver platter. The audience must engage with the story at its own pace, which may take some time, but films like this are crucial.

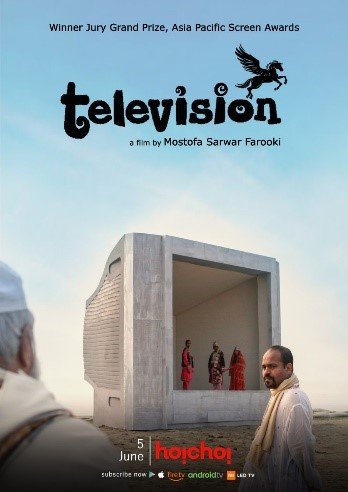

Television

Farooki’s film Television produced a world of illusions about Bangladesh’s rural population. The plot centers on a Muslim community in Bangladesh’s rural village of Noakhali. The chairman inhibits people’s inventiveness because he feels it is an adversary of God Almighty. The villagers tried numerous alternative forms of entertainment, but the chairman believes that everything is against God, so he dismisses all of their ideas. With this intriguing plot, the film opens up a whole new universe, not just for the Bangladeshi audience but also for the international public. Television provided a candid portrayal of Bangladeshi life to a global audience. Farooki successfully produced a societal satire with a triangular love story and a caustic, dark sense of humor. The cinema’s camera work was unique, as were Farooki’s previous works. The handheld shots used throughout the film added a rustic, earthy feel to the plot. Additionally, the use of nature to make the shots clearer and better was outstanding, providing a comprehensive overview of Bangladesh’s natural beauty and rural areas in the film. For some reason, this camera approach reminds me of Italian Neorealist films. In those films, we often saw the utilization of long views to depict the country’s surroundings.

Epilogue

Overall, Mostafa Sarwar Farooki is attempting to elevate Bangladeshi productions to a new level in global cinema, and in doing so, he has established a place for himself. Even though the Bangladeshi people may not widely acknowledge or appreciate his films, he is determined to persevere. He is creating and telling the stories he wishes to share with the world, and he is doing it in a remarkable fashion. His innovative storytelling style and filmmaking skills are thriving in the industry, influencing many young people. Ultimately, every filmmaker aspires to have his work appreciated.

Farooki’s films, in my opinion, offer a fresh perspective on Bangladeshi life and culture. His works evoke the true sentiments of our society’s citizens, which is what I admire about him. He portrays the tender and fragile aspects of a masculine character in ‘Doob’, while in ‘Television’, he depicts an even more intricate subject: the clash of religious faith and imagination. All of these emotions have been experienced or witnessed in our lives, but we have never thought to express or share them with the rest of the world. Mostafa Sarwar Farooki, therefore, is a true jewel in the Bangladeshi cinema industry right now.