Whereas cinema was designed to depict real-life scenes and occurrences, what it actually does is stereotype a variety of things, including gender roles, religious practices, communities, and more. When it comes to war-based movies, it follows a constant trend through which they trigger audience emotions and try to manipulate their attitude towards liberation war plot.

When liberation war films were designed to recreate war scenes, what they actually do is distort the core of our war history through their politically constructed reality. Filmmaker’s main concern is to impose their own ideology upon the audiences and convince them to live up to their set benchmark; our liberation movies only support for that matter.

In these war films, mothers, wives, and girlfriends are seen in the beginning scenes of the story, especially when the soldiers leave their homes for the battlefield. They are seen again when they read letters sent by their loved ones from the battle, for example in The Thin Red Line (Malick, 1998), We Were Soldiers (Wallace, 2002), to portray the dichotomy of the reality of those who are fighting, the soldiers, and those who are not, mainly the women. Finally, these characters may be seen at the end of the war when the soldiers return home. We are used to the fact that women characters ought to be portrayed of either as a victim of the war or as a wife/mother not directly involved but emotionally compromised by the events taking place around her.

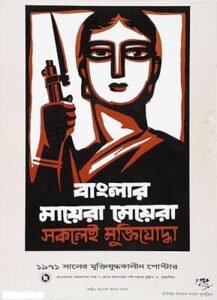

Under political suppression, mainstream media has successfully created fragile images of women and has portrayed men as strong, fierce, and powerful. In these films, we would see women as any role starting from being nurses, mothers, wives, lovers, resistance fighters, and of course, frail victims other than as a soldier. We all know battlefield scenes are reserved for men only. Clearly, deadly gunfight sequences have entertained audiences for a film to be commercially successful but typically distorted the background of 1971. Women that time have not only provided food and shelter for the Mukti Bahini (War soldiers) but also laid their hands upon rifle and guns. These commercial films have entirely failed to portray the role of women in the war zone. And this indicates the negligence of media towards women. Was losing their honor (who were sexually abused) for nothing!!!!

Men sacrificing their lives in the war have been entitled as martyrs, while women sacrificing their lives in the same war have been termed as Birangonas. The mainstream history of the liberation war states that “Bangladesh has achieved the independence from the blood of three million martyrs and the loss of ijjat (loss of chastity) of two hundred thousand women” (Sarkar, 1998:2). The evidence of wartime torture gave men the honor of muktijoddha (war hero), whilst the same evidence of torture has been perceived as women’s loss of honor. It is what happens when the patriarchal society has control over language. Women were never represented as freedom fighters. Whatever their roles in the films, had any woman been raped, she either had to die, become insane, or become invisible; she had never been represented as a normal human being. As the years passed by, war films of Bangladesh show a gradual decline in the active participation of women in the war.

What I am concerned about is the cinematic representation of the Liberation War in Bangladeshi Cinema. There is no dilemma encompassing men’s role in the Liberation War. The only question mark is about women’s contribution. And it won’t be very surprising to raise doubt now on women’s participation during wartime where all we have seen so far is women being portrayed as helpless prey to the ravages of war. Things are not very different in terms of character portrayal when it comes to the first-ever Bangladeshi cinema shortlisted for Oscar nomination in the Foreign Language category, “Matir Moina” in English as The Clay Bird. In one of the movie sequences from Matir Moina, where we observed the female character tells her brother-in-law, a political activist, “I do not have any war.” Her dialogues impose the idea that women are too naive to understand that wartime situation as she was caught reminiscing her childhood very fondly and was unaware of the socio-political conflicts happening around her. This initiates the ideology that, women were simply reacting to the wartime situation and their participation was consciously absent for that matter. For a short intro for those who do not know, the film was set in the late ’60s, before Bangladeshi independence from Pakistan; the film deals with a young boy named Anu, in a Bangladeshi small-town, with his strict and deeply religious father, mother, and little sister.

I doubt there is a single cinema lover in Bangladesh who has not seen Zahir Raihan’s Jibon Thekey Neya (1969). But all we can grasp from the plot itself is, women are either impractical, stubborn, and evil herself or soft, good, and family-orientated. This pre-liberation film has beautifully captured the socio-political situation using metaphor but failed to keep the real essence of women at that period of time. Though the film showed the nation fulfilling its aspiration to become an independent nation, this calling was not meant for the women of the film. This framework of sons preparing for the country’s liberation war, not daughters, continued in the post-liberation films as well.

Socially weak position constructed for women based on the rape experiences during the war. Rape scenes became essential parts of war films (1972-1975). In the first film made on the Liberation War, Ora Egaro Jon directed by Chashi Nazrul Islam (1972), the female protagonist who worked in a camp as a nurse, was raped; and the side female character died being raped in a Pakistani bunker. From 1972, nearly all the war films of Bangladesh contained at least one rape scene. And these became a trend for the wartime films to be commercially successful. Except for Guerrilla, women’s participation as direct freedom fighters is completely absent in war films. The nation had to wait for 40 years to get an on-screen female freedom fighter. However, she had to kill herself at the ending scene to be recognized as a freedom fighter.

War film has always been a popular genre all over the world. Generally, it contains a certain formula, suggested by Sobchak as a narrative where “a group of men, individuals are thrown together from disparate backgrounds must be welded together to become a well-oiled fighting machine”. We are more prone to look for the cultural and political representation of war times in Hollywood movies. Hollywood war movies as easy to identify through convention including a plot beginning with training and following a specific unit into battle, troops depicted as heroes; the enemy fanatical. A socially constructed structure or convention refers to the ideological meaning that “woman” is for men. And female characters are better off passive and powerless. This is what appears to be pleasurable.

War film has always been a popular genre all over the world. Generally, it contains a certain formula, suggested by Sobchak as a narrative where “a group of men, individuals are thrown together from disparate backgrounds must be welded together to become a well-oiled fighting machine”. We are more prone to look for the cultural and political representation of war times in Hollywood movies. Hollywood war movies as easy to identify through convention including a plot beginning with training and following a specific unit into battle, troops depicted as heroes; the enemy fanatical. A socially constructed structure or convention refers to the ideological meaning that “woman” is for men. And female characters are better off passive and powerless. This is what appears to be pleasurable.

The movie “Meherjaan” is an example of what happens to a movie if it does not follow the dominant narrative of war or the social construction of gender. This film – directed by a female director Rubaiyat Hossain – portrays a wartime story of the love of a local girl (Meher) with the enemy soldier and the agentive role of raped women (Neela) who seeks revenge by joining the war. Moreover, there were issues like the visibility of women’s sexual desire, homosexuality, freedom fighter’s tiredness about fighting, and an indication of the wider structural context within which violence against women is normalized in a non-war situation. Because of this controversial plot, it was banned.

Characters like Khosru influence the society to think that women were only the supporters of Bir Muktijoddha during wartime. In a movie scene. Khosru (Ora Egaro Jon) had been observed to acknowledge the service of a cook, she replied, “You are fighting for the country, compared to that I am doing nothing”. While the implicit intention in this statement was to highlight freedom fighter’s contribution, another meaning has emerged from the practice of “private patriarchy” which considers household work as a woman’s essential duty, hence valueless. In fact, the persistent objectification of women in these films has misrepresented facts, not only in terms of our wartime ideology but also in terms of our history.

Source: Internet